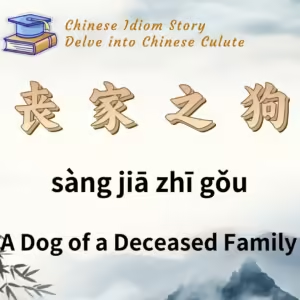

Chinese Idiom: 兔死狗烹 (Tu Si Gou Peng)

English Translation: When the rabbit dies, the dog is cooked

pīn yīn: tú sǐ gǒu pēng

Idiom Meaning: This phrase is used to describe a situation where individuals can only share hardships together but cannot enjoy successes or happiness together.

Historical Source: Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》) – Biographies of King Goujian of Yue (越王勾践世家).

Idiom Story:

Fan Li (范蠡) was a capable strategist and advisor to King Goujian of Yue during the Spring and Autumn period. When King Goujian was besieged by the powerful King Fu Chai of Wu at Mount Kuaiji, it was Fan Li who advised him to endure humiliation and bide his time for revenge. After enduring hardship and plotting for many years, King Goujian eventually defeated Wu and restored his kingdom, largely thanks to Fan Li’s strategies.

However, when King Goujian emerged victorious and became the last hegemon of the Spring and Autumn period, Fan Li chose to withdraw from court life, seeking a simple and reclusive existence.

Upon arriving in the state of Qi, Fan Li wrote a letter to his former colleague Wen Zhong, advising him to leave Yue. In the letter, he stated:

“蜚鸟尽,良弓藏;狡兔死,走狗烹。”

(When the birds are all shot, the good bow is put away; when the cunning rabbit dies, the hunting dog is cooked.)

In this context, Fan Li pointed out that once their objectives are achieved, those who were once useful or loyal might be discarded. He noted that while King Goujian was capable of enduring hardships alongside others, he could not be trusted to share in their joys or successes.

Wen Zhong took Fan Li’s advice to heart but hesitated to leave. Unfortunately, he was soon framed for treason, and King Goujian, without proper investigation, ordered him to commit suicide, stating:

“你教给我七条攻打吴国的办法,我才用三条,就把吴国灭掉了;其余四条还在你那里,你就到我的祖先那去实现它们吧!”

(You taught me seven methods to defeat Wu; I used three and succeeded. The other four remain with you, so you shall implement them in the afterlife!)

This tragic outcome illustrates the bitter truth behind the saying “兔死狗烹,” highlighting the precarious nature of loyalty and the risks faced when one’s usefulness is no longer needed. The idiom serves as a cautionary reminder of how those who once shared struggles may not be able to share in the triumphs.